When a water heater fell on him one fateful day at work, John Dias’ life was forever changed. He awoke in the hospital, partially paralyzed, and when he left, he had a prescription for OxyContin. But like so many others, his prescription became his affliction, resulting in a severe addiction and eventual overdoses.

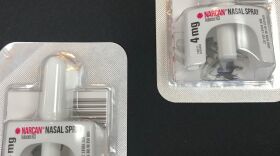

In recent years, this occurrence has become all too common, leading to the development of the antidote naloxone – the very medicine which revived Dias on two separate occasions. To find out more about his story, “Take Care” spoke with Dias, who opened up about his experience and the importance of naloxone, also known by the brand name Narcan.

After the initial injury, Dias had three surgeries on his neck and back -- two on his shoulders, and one on his elbow. With each surgery, his doctors and pain management team continued to refill his prescription. He had a written prescription for OxyContin for almost two years.

For the first year or so, Dias says, he took the painkillers as advised, but soon realized he was developing a dependence. He had a brief stint with pain medications following an injury in his early 20s, he explains, but he stopped taking them once the prescription was finished. He could recognize the same dependence developing, but when he told his doctor he didn’t want any more surgeries because he was addicted to the painkillers, his doctor and pain management team “kicked me out of their office and told me I was a liability,” he says.

Dias says he was escorted out of the building without any mention of addiction services. He had hoped that expressing his concerns to his doctor would merit a referral to a rehabilitation center, but he says that is far from what he says he got.

With no more access to the written prescription, Dias turned to the streets to find painkillers. And at this point, he says, it was no longer about the pain. He was addicted. And when he couldn’t afford the price of pills, heroin became a cheaper alternative. For the cost of one pill, he could get an entire day’s worth of heroin. And this went on for 6 months.

He overdosed twice, and was revived by Narcan administered by paramedics in both instances.

“My face was blue and my lips were white when they found me. I had vomit all over me and I was choking on it,” he says.

After the second overdose, Dias was able to get clean. And what needs to be understood, according to him, is that people of all walks of life can become addicts.

“When you are addicted, you are a different person,” he says.

Were it not for Narcan, Dias says he would have died. Since its development, it has saved countless lives, but not everyone is so lucky. In fact, Dias says his own brother might still be alive had there been Narcan available at the time of his overdose. But unfortunately, says Dias, there wasn’t.

As the number of overdoses continues to soar, accessibility to Narcan is becoming increasingly important. Those in the public health sector, like Baltimore Health Commissioner, Dr. Leana Wen, are pushing for Narcan training in their cities, to reduce the number of lives cut short as a result of drug abuse. Addiction is a disease, but through proper education, training, and availability to Narcan, health officials hope to prevent people from overdosing and revive those who do.